News & Insights

Associate Article: Examining Co-production Part 1 – The Right Circumstances

As a long-time advocate and practitioner of the involvement of people in delivering health and care services, I have recently noticed how often research, projects and services need to re-learn the same lessons which I thought were well known, particularly around the area of co-production. There seems to only be an informal sharing of good practice and experience in health and social care, so I undertook to review what is available, to see how we might get good practice to gain traction and become normal practice.

Although not a formal literature review, I used a wide range of sources I have gathered over the last three years as I have stumbled across them, together with a search of material available online, for example via the Public Experience Library. I chose to focus on information from the last 10-15 years, which I assumed builds on previous material and learning. I only reviewed information on co-production in providing wider services, not in individuals co-producing their own care and support.

The Role of Co-production

Co-production is a term used more widely in health and social care than ever before, and whilst there are lots of examples of co-production in action, it remains challenging to find examples that fulfil everyone’s interpretation of what good co-production looks like. A simple internet search for ‘NHS Co-production examples’ returns sites that show positive patient involvement projects, but that would not meet the criteria for co-production set out in this article.

Definitions of co-production exist but articles such as an example by Miller & Wyborn[1] highlight that, ‘Confusion persists over precisely what co-production means and how to apply it’

The literature review ‘The Value Of Co-Production Within Health and Social Care’, carried out jointly by Healthwatch Suffolk and the University of Suffolk[2], provides a great history of the development of co-production in public services.

It is helpful to revisit that Elinor Ostrom et al[3] were the first to focus on co-production in public services, but reading their work now, it does not feel as evangelical as current discussions about co-production. The report highlights the value of the service consumer or user: ‘Students can supply much of their own education in the absence of teacher inputs, but teachers can supply little education without inputs from students. Police have very little capacity to affect community safety and security without citizen input, yet citizens are able to protect their own homes to a degree in the absence of regular police inputs.’

Ostrom at al also state that ‘decisions about adding or reducing regular producer or consumer producer inputs can be made independently, guided only by their marginal impacts on the level of output,’ indicating that co-production should only be employed when the impact warrants the level of input. They also highlight that co-production is likely to function best at a neighbourhood level, with the benefits being lost at larger scales of service production.

These are important points at a time when co-production is seen as the gold standard for all public involvement.

The work of Arnstein has been built upon to refine the ladder of participation, for example the Ladder of Co-production[1], but this may have led to the perception that this is a hierarchy rather than a range of approaches to deploy in different scenarios.

As NESTA[2] state: ‘Co-production has emerged from a rich and diverse literature and practice; today it has parallels, for example, in asset-based community development. However, there has been some confusion between co- production and service-user design, user ‘voice’ initiatives and consultation exercises. Although co-production encompasses all of these things, it cannot be reduced to any one of these approaches. To fall back on a well-worn cliché, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

At its most basic, co-production of public services is about ‘action’, for example people (including professionals and people who use services) coming together and producing a service or an outcome through the medium of public services.’

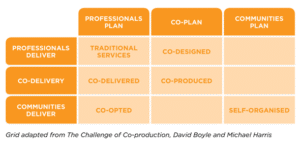

Nesta have produced a useful visualisation of different approaches:

My exploration of current thinking and my experience of the benefits and challenges of co-production indicate that it is an approach to aim for, but only in the right circumstances. The risk of applying the name inappropriately is that the right approach in the right circumstance is not celebrated, but seen as failing to be co-production.

The right circumstances

Below are some potential criteria for evaluating whether co-production is appropriate:

- Everyone involved has the authority to move outside of the normal way of doing things.

A review of six experience-based co-design projects in Australia found there was significant tension when health professionals and service users came together to work collaboratively and were required to move out of traditional ways of working and mindsets. [1] Transferring and sharing power was difficult and for the most part remained unsuccessful. This was made more difficult to achieve by the hierarchical decision making processes the projects had to follow.

In analysis of the use of their Experience-based Co-design Toolkit[2], the Point of Care Foundation found that you need more than the approval of your senior leaders; you’ll need their active involvement and visible support.

Furthermore, a study of 107 Quality Improvement projects[3] illustrated that the closer the personal involvement in the implementation process, e.g. in a microsystem, the greater the reported experience of success. This meant that leadership in the wider macrosystem that were more distant from the project did not see the benefits as enthusiastically, which risks user involvement being reasoned away as only adding workload without returning any value, and it may, therefore, be poorly supported.

- The aims will be shared by everyone

Th above sources also highlight that what you are hoping to achieve with the co-production process must be what is important to everyone involved. Everyone’s input must be valued equally and so the aim of the project cannot be driven solely by an organisations desire to change a service or an individual’s desire to act on their experiences.

- The right scale

Given the requirements for 1 and 2 above, and the original thoughts of Elinor Ostrom on neighbourhoods, it must be questioned whether co-production is possible at a wide geographical or strategic level in health and social care. If co-production is being considered at a borough or regional level, will you genuinely be able to get senior leadership buy-in or agree the aims amongst the range of people that would need to be involved?

- The intended outcomes are clear and can be measured

Once the shared aims are clear, can the changes you aim to bring about be measured to show progress? Outcomes should also include changes in knowledge, confidence, culture and behaviour, how can they be measured? As the Point of Care toolkit states, to effectively measure you must know what success looks like, understand and change what matters, and to evaluate for learning not just what happened.

- There is sufficient resource, time and support

A range of sources refer to the time and level of resource needed to make co-production a success including:

- Ensuring everyone understands the process

- Building relationships

- People joining with the right skills, knowledge and experience

- Frequency of coming together

- Support for everyone to participate fully

A review of a co-production project called Co-PARS in Liverpool[1] states: ‘It is important that researchers (and stakeholders) appreciate the substantial time and resources that are required to meaningfully co-produce a health service/intervention. This may in fact save time and resource in the long-term by reducing the translational time lag from evidence generation to changing practice’.

- Everyone involved will be included in implementation and evaluation.

The key thing that makes co-production different to codesign and other forms of involvement is the role of people in the delivery of the service. How realistic this is will be key to deciding if you should embarking on co-production. How can the assets of people and communities be part of providing the service? This highlights the importance of seeing people as having strengths, knowledge and experience, and not be seen in a deficit model as needing help and support, as set out by Nesta.

In Part 2, I’ll be looking at the right preparation to undertake co-production.

Do you have examples of co-production you want to share? Do you agree with the findings of this review? I’d love to hear from you: Steve.Inett@consultationinstitute.org

[1] https://www.thinklocalactpersonal.org.uk/Latest/Co-production-The-ladder-of-co-production/

[1] Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories Clark A Miller, Carina Wyborn, Environmental Science & Policy Volume 113, November 2020, Pages 88-95

[2] The Value Of Co-Production Within Health and Social Care Reviewer, author & co-editor Susan Conquer

(Co-production Coordinator, Healthwatch Suffolk), Co-editor Luke Bacon (Research Officer, Healthwatch Suffolk), Peer reviewers from the University of Suffolk Dr Will Thomas (Associate Professor), Sophie Walters

(Citizen Involvement Coordinator), Professor Helen Langton (Vice-Chancellor and CEO) 2021

[3] CONSUMERS AS COPRODUCERS OF PUBLIC SERVICES: SOME ECONOMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL CONSIDERATIONS Roger B. Parks, Paula C. Baker, Larry Kiser, Ronald Oakerson, Elinor Ostrom, Vincent Ostrom, Stephen L. Percy, Martha B. Vandivort, Gordon P. Whitaker, and Rick Wilson Indiana University and The University of North Carolina 1980

[4] https://www.thinklocaactpersonal.org.uk/Latest/Co-production-The-ladder-of-co-production/

[5] People Powered Health Co-production Catalogue Nesta April 2012

[6] Anyone can co-design?”: A case study synthesis of six experience-based co-design (EBCD) projects for healthcare systems improvement in New South Wales, Australia, Tara L. Dimopoulos-Bick, Claire O’Connor, Jane Montgomery, Tracey Szanto, Marion Fisher Agency for Clinical Innovation, New South Wales, Australia 2019

[7] https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/resource/experience-based-co-design-ebcd-toolkit/

[8] How might patient involvement in healthcare quality improvement efforts work—A realist literature review Carolina Bergerum RN, RM, MSc, Johan Thor MD, MPH, PhD, Karin Josefsson RNT, PhD, Maria Wolmesjö PhD 2019

[9] Multi-stakeholder perspectives on co-production: Five key recommendations following the Liverpool Co-PARS project Benjamin JR Buckley, Jacqueline Newton, Stacey Knox, Brian Noonan, Maurice Smith & Paula M Watson 2022