News & Insights

Co-production week! Balancing co-production and accountability in public engagement and consultation processes

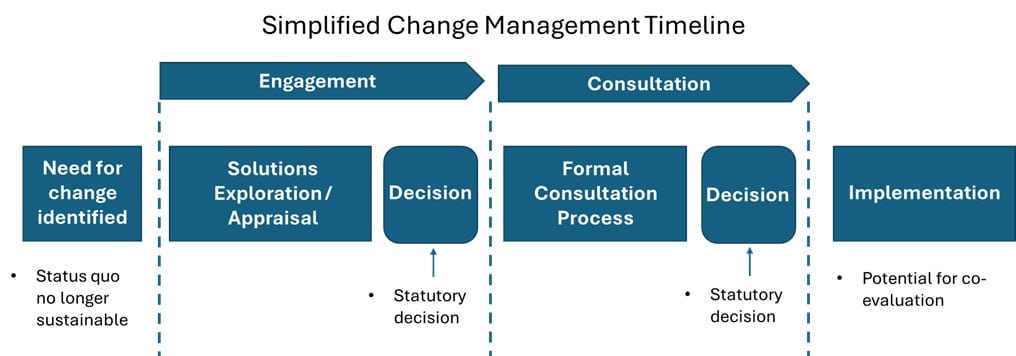

When we describe the best practice process of consultation and engagement, we very often refer to the change management timeline, which sets out all the complexity in detailed steps. However, in some cases, we also look at the simplified change management timeline as shown below.

This simpler presentation is particularly useful when we consider the potential role co-production plays in the process. We can clearly see that the process calls for decision makers to make decisions in ways that are bound by regulation, statute and accountability to the community served. These constraints can limit the flexibility of the co-production process and restrict the range of possible outcomes, making it difficult to fully incorporate stakeholder input. Arguably, these limitations mean that co-design is possible, whereas co-production cannot be delivered.

This goes to the heart of one of the questions we are most often asked in training sessions or when supporting organisations implement co-production, which is ‘what’s the difference between co-production and co-design?’ To some extent there is a rationale to support the statement to the effect ‘…it doesn’t matter as long as people feel they are valued in an environment that shares power and decision making.’ This is hard to argue with, and yet conversely easy to disprove, and is of particular importance in the world of formal consultation.

To expand on this we can draw on the definition provided by Think Local Act Personal[1] in their ladder of participation model, which is:

Co-production is an equal relationship between people who use services and the people responsible for services. They work together, from design to delivery, sharing strategic decision-making about policies as well as decisions about the best way to deliver services.

The key part of this in the context of our discussion is the last part of the final sentence about sharing decision making on policy direction and service delivery. When we compare and contrast this with the definition of co-design:

People who use services are involved in designing services, based on their experiences and ideas. They have genuine influence but have not been involved in ‘seeing it through’.

We can see that this more accurately describes the potential for co-productive activity in the engagement and consultation cycle. In other words we co-design in the process due to the legal responsibilities and governance/accountability structures of statutory public service organisations, irrespective of sector or purpose. This presents a power imbalance at the point of decision that mitigates against co-production.

Returning to the point ‘why does this matter as long as people feel power is shared equally?’, it becomes clear that this is only likely to be true up until the point of decision. This becomes important when we consider that any formal consultation implies a contract between consultee and consultor. If the consultor is promising to co-produce the solution then they must be prepared to be party to co-decision making, which will not be possible because of governance, accountability and statutory requirements. This failure to keep to the contract has not been challenged or tested, but the potential exists and as co-production is mandated in more and more consultation settings the potential grows.

If this raises any questions for you around your approaches, or if you’d like to learn more or are interested in the practical support and training we can provide around co-production, please get in touch with our team here.

[1] LadderOfParticipation.pdf (thinklocalactpersonal.org.uk)